Anchor's Away!

April 1, 2015

The Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research Study

IT’S INDISPUTABLE THAT HAVING A CELEBRITY SPOKESPERSON benefits any cause. Scott Hamilton defeated testicular cancer, Kathy Bates overcame ovarian cancer and is now fighting breast cancer, and two of the original Charlie’s Angels, Kate Jackson and Jaclyn Smith, are breast cancer survivors.

But it was the third angel, Farrah Fawcett, who didn’t survive her cancer, dying at the age of 62 in 2009 of anal cancer. Fawcett became the one who took this particular cancer from being “unmentionable” to finally grabbing the attention of the public. Now, it even has an awareness day—March 21, 2015 is the second National Anal Cancer Awareness Day—and a foundation, the HPV and Anal Cancer Foundation.

There also is the new International Anal Neoplasia Society, the world’s first professional society devoted to the prevention and treatment of AIN and anal cancer. Its mission is “to provide a forum for individuals with a broad spectrum of background, viewpoints and geographic origin, an exchange of ideas and dissemination of knowledge regarding the pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of anal neoplasia.” Informational resources are available on the website for both medical providers and patients (http://ians.memberlodge.org).

Stigma again

The stigma surrounding anal cancer is similar to that associated with HIV—both leave those with the disease open to the judgmental assumptions of others about their sexual activity, their self-respect, even their morality. Similar to HIV, the only way to combat such stigma is for those with the disease to refuse to accept ignorance, fear, and judgment as reasonable reactions to conditions caused not by specific behaviors, but by viruses.

The most dangerous thing about the stigma associated with any disease is that it often deters people from getting the screening tests that would then lead to treatment. In the case of anal cancer, the human papilomavirus (HPV)—specifically the HPV 16 strain—is responsible for 90% of all anal cancers and there are several screenings that can detect abnormal cells caused by HPV that can lead to cancer.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), with almost every sexually active person having it at some point. In most cases, the virus will be cleared by the body’s immune system within two years and there are currently two FDA-approved vaccines that guard against HPV, Gardasil™ and Cervarix™. They both prevent infection by strains 16 and 18; Gardasil also provided protection against strains 6 and 11.

Despite these advances, anal cancer rates are increasing, with an estimated 7,210 people diagnosed in 2014 with anal cancer in the U.S. Of those, 62% will be women and 38% will be men, with the highest rates occurring among HIV-positive gay men.

Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN)

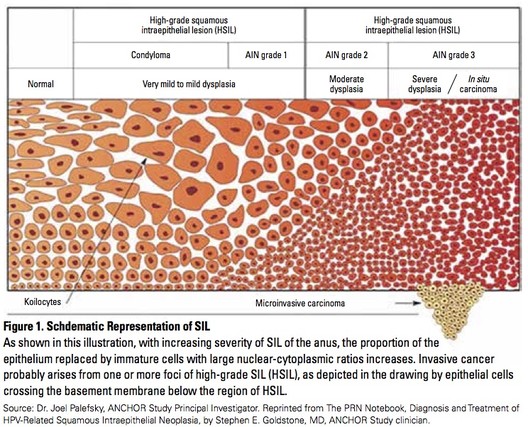

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)—abnormal cells in the skin just inside or immediately outside the anus—is classified in three stages:

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)—abnormal cells in the skin just inside or immediately outside the anus—is classified in three stages:

- AIN 1 (LSIL or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions) is least severe, mild dysplasia (proliferation of cells of an abnormal type), and can appear like warts.

- AIN 2 (HSIL, or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions) is moderate dysplasia and may progress to anal cancer over time.

- AIN 3 (also HSIL) is severe dysplasia and may progress to cancer.

There is no standard treatment for AIN at this time, as it is difficult to predict which cases will regress if left untreated.

Screening for Anal Cancer

There are several types of cancers that can involve the anal region: squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common, cloacogenic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma. Most have no symptoms in the early stage and symptoms that do appear may be mistakenly thought to be due to other conditions. Thus, attention to patient symptoms and subsequent evaluation for anal cancers is a very important aspect of HIV-patient care.

Screening methods include:

- Visualization of the anal-rectal area for any abnormal skin changes or lesions

- The basic DARE (digital ano-rectal examination), in which the clinician inserts a gloved finger into the anus to detect any abnormalities.

- Anal Pap smears, in which the anus is swabbed to collect cells for examination to detect abnormalities that may be precursors to cancer.

If abnormalities are detected by screening, high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) is recommended, in which an anoscope and a colposcope are used to determine where abnormal anal tissue is located and to guide biopsies. Some clinicians and patients may believe that HRA is an accepted screening tool. However, it must be noted that most health plans will NOT pay for HRA if it is done for screening and not diagnostic purposes. If cancer is confirmed by biopsy, the stage, or the extent of the spread, is determined and treatment options are decided. Generally, the earlier the stage at diagnosis, the easier and more successful treatment will be.

The Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) Study

“If you’re HIV-positive, you owe it to your anus to get checked out. It could literally save your butt.” So says the homepage of the ANCHOR Study website (www.anchorstudy.org). Who could resist?

As with any study of this kind, it is challenging to recruit as many qualifying participants as we need. Across the United States, 5,085 men and women will be enrolled in this study. We have tried to give potential subjects the information and motivation they need to sign up, show up, and complete the study.

Committing to five years of monitoring is not easy for many patients. However, the key outcome for the ANCHOR study is to determine if screening and treatment of high-grade SIL is as effective in preventing anal cancer as was found with screening and treatment for cervical cancer in women. Not only will this save lives, but 3rd party payers will be more likely to cover the cost of screening for anal cancer.

To qualify for the study, candidates can be either male or female and must:

- be at least 35 years of age

- be HIV-positive

- never have been vaccinated against HPV

- never have been treated for anal HSIL

- never have had cancer of the anus, vulva, vagina, or cervix.

- have anal HSIL (tests for this will be done)

Participants will be randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1 (Active Monitoring) will not have any anal HSIL treatments. Group 2 (Treatment) will have treatment of anal HSIL chosen by the patient and doctor doing the study.

Active study sites are located in:

- Boston:

- Boston Medical Center, 85 E. Concord Street, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02118 - Drs. Ami Multani and Lori Panther

- Fenway Health, The Fenway Institute, 1340 Boylston, Boston, MA 02215; 617-414-5149 - Dr. Elizabeth Stier

- Chicago

- Anal Dysplasia Clinic MidWest, 2551 North Clark St., Suite # 203, Chicago, IL 60614; 312-623-2625 - Dr. Gary Bucher

- New York:

- Cornell Clinical Trials Unit, Chelsea Research Clinic, 53 W 23rd St, 6th Fl, New York, NY 10010; 212-746-7204 - Dr. Timothy Wilkin

- Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein, College of Medicine, 1695 Eastchester Road, 5th floor, Bronx, NY 10461; 212-746-7204 - Drs. Mark Einstein and Rebecca Levine

- Laser Surgery Care, 420 W 23rd St, Suite PB, New York, NY 10011; 212-242-6500 - Dr. Stephen Goldstone

- San Francisco:

- UCSF Mt. Zion Medical Center, 1701 Divisadero St., Suite 480, San Francisco, CA 94115; 415-353-7443 - Dr. Joel Palefsky

Check the ANCHOR website for future active recruiting sites.

Please help

Medical history is made when people have the courage and dedication to lend their bodies to research. Without clinical trial participants, and the activism of many of them, HIV treatment may never have gotten to single-tablet regimens from AZT monotherapy and hepatitis C treatment might not evolved past interferon. Without effective studies to discover both physical and but social determinants of health, how can those suffering from any illness, including the socially disadvantaged ever have equal access to healthcare?

Hopefully, clinicians will encourage their patients living with HIV who meet all the study’s eligibility criteria to consider becoming one of the unsung heroes who will make it possible for us to prevent anal cancer. If you are providing care for patients with or at risk of AIN and anal cancer, encourage them to contact one of the study sites and make a difference in the fight against this disease.

One of the ironies of life is that having an illness that many others have creates a community of sorts. Farrah Fawcett said, “This experience has also humbled me by giving me a true understanding of what millions of others face each day in their own fight against cancer.” And it’s awe-inspiring to witness an AIDS ride or an MS or breast cancer walk, to see people supporting those they care about as well as perfect strangers they’ll never know. On March 21, honor Anal Cancer Awareness Day by talking to your patients – or your own doctor—about the risk of AIN and having a screening.

How wonderful would it be if instead of coming together in support of those struggling with a disease, we could come together in celebration of the end of it?

About the Author Gary Bucher, M.D., FAACP