What is HPV?

HPV (Human Papillomavirus) is the name of a group of sexually transmitted viruses that includes more than 80 different strains or types. HPV is one of the most common STDs in the world. HPV is the cause of warts which usually appear in the groin area. HPV strains 16 and 18 are more likely to cause cancer in the cervix and anus. Most people who become infected with HPV will not have any symptoms and will clear the infection on their own. HIV positive people may take longer to clear the HPV infection, increasing their risk of developing cancer.

How do you get HPV?

HPV can be passed from person to person, even when there are no signs of infection. Although condoms do reduce the chance of infection, they don't offer complete protection against the virus since HPV can be easily spread by skin-to-skin contact with areas of the body not covered by condoms. Because HPV is spread through skin-to-skin contact, both men and women who are sexually active are at risk for getting HPV .

Do a lot of men have HPV?

Yes, men who have sex with men do have higher rates of HPV infection than heterosexual men. At some point in their lives:

- At least 50 percent of all sexually active men get HPV

- More than 65% of HIV negative gay men get HPV

- More than 90% of HIV positive gay men get HPV

What are the signs of HPV infection?

Genital warts are the most easily recognizable sign of HPV infection. Genital warts are single or multiple growths that appear around the anus or on the penis, testicles, groin or thighs.Warts may appear within weeks or months after sex with someone who is infected. Sometimes, the virus remains 'silent' in someone's system -- in these cases, the people never develop warts even though they have the type of HPV that causes them. Genital warts can be surgically removed, frozen off or treated with medication. Warts sometimes do return, especially within the first few months of treatment.

Is there a cure?

Unfortunately, there is no cure for HPV. The good news is that most people who become infected with HPV clear the virus on their own (which means that the virus won't cause them any long term harm). There are several vaccines to prevent HPV infection in boys and girls. These vaccines must be given before a person is exposed to HPV. But once a person is exposed to HPV, there is no cure, just treatment of the warts and lesions caused by HPV.

What is the link between HPV & anal cancer?

Most HPV infections do not cause cancers, but some do. The types of HPV that can cause genital warts are not the same as the types that can cause anal cancer. In a small number of people, certain strains of HPV can cause abnormal skin cells to grow in the anal canal. Sometimes, these changes can gradually worsen and develop into pre-cancerous cells. If left unchecked, in a small proportion of people, anal cancer can develop over a period of many years.

Is there a test to screen for HPV-related cancers in men?

Unfortunately, there are no approved tests to detect the early evidence of HPV-related cancers in men. Women, however, do have an approved test -- the PAP smear. Once abnormal growths have formed, which can take 20 - 30 years, they can often be detected during a routine digital rectal exam or anoscopy.

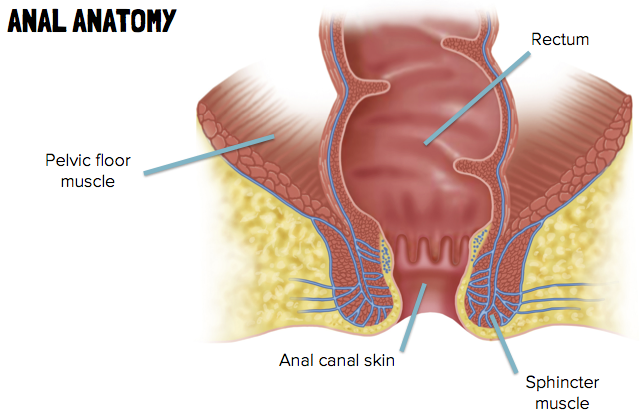

The anus is the very end of the digestive system, just below the colon and the rectum. Anal cancer is cancer of the skin lining the anus. It is different from colorectal cancer, and sometimes missed during routine colonoscopies (exams to look for colorectal cancer).

The anus is the very end of the digestive system, just below the colon and the rectum. Anal cancer is cancer of the skin lining the anus. It is different from colorectal cancer, and sometimes missed during routine colonoscopies (exams to look for colorectal cancer).